Heindijk: a neighbourhood in Rotterdam to be fossil-free by 2027

© Richard Ciraulo

In the Netherlands, decarbonisation is often approach through the district perspective. It favours thus affordability, inclusiveness, and achievability. This is also the best way to minimise inconvenience for residents and the total costs, while maximising the potential combinations with other ongoing or planned projects. The neighbourhood of Heindijk, in Rotterdam, consists in 638 houses and 7 utilities. The size of the neighbourhood being ideal, the city decided to make it a pilot project for fossil-free districts by 2027. A great source of inspiration for Decarb City Pipes 2050 partners, who were welcomed there on 20 April 2022 by Marie-Emilie Ingen Housz, Cleo Pouw, and Lydia Hameeteman, from the city of Rotterdam.

Carefully choosing a pilot area means having a holistic approach

The Heindijk neighbourhood is a strategic area with which to start: not too big, quite a heavy CO2 emitter, and urbanistic works are planned to redesign the public space and replace the old sewage systems. A good opportunity to block the streets once and minimise inconvenience for its inhabitants! The Energiehuis is a true meeting point for the residents of the neighbourhood. It is a place where you can, of course, gather information on energy. It is also a socio-cultural place, where elderly people can come and play cards or just gather for a chat. Finally, it is a place where social workers support citizens in their job or training search. And because all these stakeholders are gathered in the same place, they inevitably interact, favouring for instance job searches or trainings related to energy or to accompanying elderly people. In a word, the Energiehuis is a neuralgic place, where many profiles coexist and interact. An ideal place to reach a large variety of citizens and embodying decarbonisation in the daily matters of the neighbourhood.

Becoming fossil-free by 2027: where to start?

The daily matters of the neighbourhood are actually more important than expected, when it comes to fighting climate change, and the city realised it quickly. Even though the goal of the pilot project in Heindijk was simple: to have a system which is affordable for everyone, at the lowest cost, it could not start immediately. Before being able to catch the attention of residents on the question of decarbonisation solutions, there was one problem which was occupying every conversation and making it impossible for residents to discuss anything else. This problem took the form of a fence which needed to be removed, as it had been illegally installed and was dividing the neighbourhood in two. Intense discussions with the city took place to finally solve the issue. The real decarbonisation work could then start.

Rotterdam. Make it happen.

The city of Rotterdam has a motto: “Rotterdam. Make it happen”, and Heindijk is no exception to this. After ensuring that residents are in proper conditions to consider the decarbonisation matter, the city could focus on the next steps: the connection of buildings to district heating, which is the less costly solution to phase-out fossil gas according to its techno-economic study.. They analysed the customer journey that residents should make to switch from gas to district heating and designed a communication strategy including a lot of direct contacts with and visits to inhabitants. The different contacts with inhabitants showed that cooking was quite a sensitive point: residents had a strong attachment to their gas stoves. Moving to an electric one was a major barrier for citizens and thus for the project. The city of Rotterdam organised then 3 cooking workshops on cooking on electric stoves. In parallel, the city could rely on one of the inhabitants of Heindijk, Frank, who, with the support of the city, decided to publish a cookbook featuring the different cultures in the neighbourhood. The cookbook was distributed amongst residents and also helped raising awareness on electric stoves. Frank was one of the first to adopt electric stoves when he was given the chance.

Once this barrier was down, a choice map was designed. to accompany the offer. It gathered five options: a complete fossil-free system at flat-level, only district heating for heating space, only electricity for cooking, all electricity, or decide later. District heating being present in Rotterdam for already some years, most of the inhabitants are familiar with the technology, even though it looks more old-fashioned compared to electricity in their eyes. Yet, when looking at costs, the whole electrification option is more complex and expensive.

Betting on restricted offer, in choice and time, to create desire

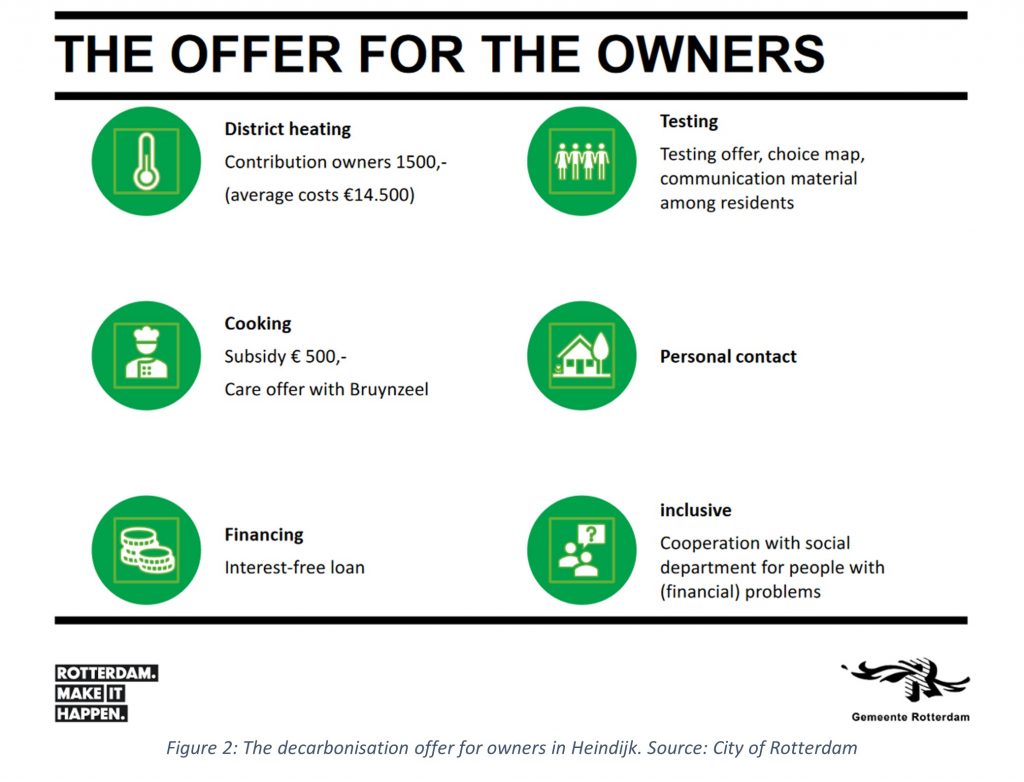

The city also reflected on the offer it could make, together with the energy provider, to the homeowners:

The strategy chosen by both the city and the energy provider was clear: there will only be two moments to decide to connect to the district heating network. Either in 2021, or in 2027, when it becomes mandatory for everyone to become gas free. An early connection makes it cheaper for energy companies, hence the possible support received by homeowners in the city offer. To make it happen in 2021, at least 30% of participation was needed. Finally, more than 70% of buildings chose to switch to district heating. The initial reflection time was of 4 months, but even after two years, some people still expressed their interest – even though too late.

This fact clearly underlined the role each inhabitant plays on his or her neighbour in terms of acceptance and forced the city and the energy provider to adopt a house-by-house approach. This is especially critical when it comes to the choice of connection methods. Indeed, one rejection of the connection may mean a different (more complicated) way for other apartments in the buildings to be connected to the network.

The fossil-free strategy in Heindijk: a success requiring a lot of time, patience, and interactions

Overall, the Heindijk pilot project turns out to be an inspiring case for the decarbonisation of districts, embracing a holistic and inclusive approach. The first takeaways from the experience are quite positive. You just need to meet some of the residents, like the Decarb City Pipes 2050 partners had the chance to, to confirm it. They gladly showed the works which have been done and took the time to chat about their experience. The main highlights, reported by the different stakeholders, include: the solid partnership between the city and the energy provider, the emphasis on personal contacts, the choice map, which was designed, and the various information meetings. Tenants regretted that the information was specifically addressed to owners though. Finally, the cooperation with other departments, such as the social one, proved useful and allowed more inclusion of inhabitants.

Even though homeowners must have three different contracting parties (the city, the energy provider, and the installation company), which is seen as an obstacle, 73% of the residents of the neighbourhood are connected to the district heating network in 2022. The estimated payback is of 30 years and the high-temperature characteristic of the network does not make it mandatory to have a fully insulated house before being connected.

However, in spite of all those positive elements, the scale-up of the project in the same conditions cannot be sure yet. The possibility for the city to subsidies most of the costs was especially linked to this pilot project and has no guarantees of being replicable, despite the success. This will depend on available budget and strong political will in the city.