Keeping cool (and decarbonised) when it gets hot in cities

© Sergei A

Heat decarbonisation is receiving more and more attention. However, with the unavoidable rise of temperatures, the topic of cooling and its climate impact is also getting hotter in cities. There is a clear demand for cooling in cities – and some of them already have a district cooling network. District cooling emits less than individual cooling solutions, but how can we ensure the deployment of decarbonised district cooling?

Why decarbonising cooling systems?

The first immediate answer to this question is quite simple: because there are European targets. The proposed recast Energy Efficiency Directive sets an objective of +1.1% increase of renewable heating and cooling (H/C) per year and +2.1% increase of renewable H/C in district heating and cooling (DHC) networks per year. However, those targets bind heat and cold together, making it difficult to assess the real impact it could have on cooling.

The second answer is brought by climate change. With rising temperatures, cooling is becoming more and more relevant in many countries, not only for the industry or the service sectors, but also for residential buildings. Some cities have already started developing their own cooling networks – mind you, the ones presented below are not even from Southern Europe…

… but in Germany!

The City of Munich has started developing its own cooling network in 2014, consisting of eight groundwater plants of 16MW, and operated by Stadtwerke München (SWM), the municipal energy agency. It should triple by 2024 with a generating plant of 35MW under construction! If, at the beginning, the main use was for refrigerating technical equipment or cooling groceries, the cooling demand for comfort has been increasing.

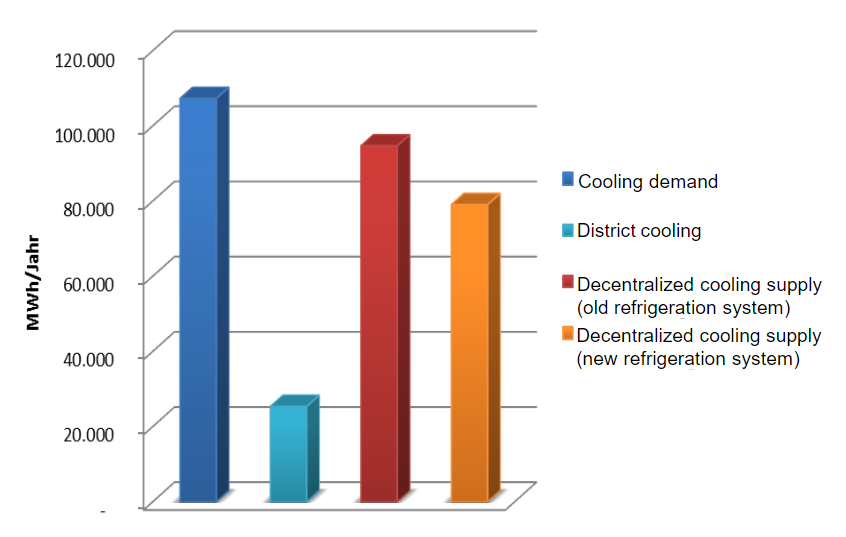

The main source is the Isar river, with remaining underground streams. It supplies both heating and cooling, built in the same system, through a heat pump. According to Patrick Krystallas, from SWM, the district cooling network even allows the city to save energy, between 50-70%, compared to decentralised cooling supplies!

How to develop an efficient decarbonised district cooling system?

There are several tools that proved useful and efficient when it comes to heat mapping and planning, but cooling has only recently been included in the scope. In the frame of a recent LIFE project, HEAT&COOL, the CEREMA has developed a tool to identify and prioritise the areas with a high potential to create, densify or extend a DHC network. Currently only focusing on the Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur Region, it is foreseen to be extended to the rest of France in 2023 and possibly replicated in other countries. The CEREMA team will publish the code used to create the tool, as well as a user manual, to allow other municipalities or countries to replicate it in their territories.

Using a multi-criteria analysis, the tool allows to obtain an aggregated and homogeneous result on the region. It makes it easier to prioritise the sectors, determine the most relevant zones to develop a DHC network, and estimate the needs of the buildings by combining different sources. The data comes from the French national database from tax services. It includes the characteristics on the buildings/ratio of consumption per square metre and supported the creation of an inventory of networks. Additional data, such as the geothermal potential, was provided by local actors. The next steps would be to include the building energy system, when possible.

Thanks to this, the process of developing a district cooling network is accelerated: the opportunity study can be skipped, jumping directly to the feasibility study!

Any pro-tips to develop your district cooling network?

Burkhard Hölzl, from Wien Energie, the municipal energy agency of Vienna, accepted to share some tips of how they set up their district cooling system in Vienna. Wien Energie is operating the four cooling plants of the Austrian capital. Three plants are currently in operation (39MW), and the fourth one is under construction (17,7MW). Contrary to Munich, the district cooling networks are separated from the heating ones. Most of the cooling is provided thanks to geothermal use of ground water around the city and, in some cases, the ground water lake is used as a seasonal storage.

So, how to stay cool when developing your district cooling network?

- Be careful before starting the construction:

- Have a clear assessment of the cooling demand (demand of specific address: type of building, how much demand)

- Explore the possibility to build a cooling plant (where to install the machines)

- Check the existing infrastructure to find cheap and favourable costs and conditions for piping

- Check the different technicalities:

- Possibility of building re-cooling systems (open cooling towers, river water, dry coolers, re-cooling via the district heating network)

- Some methods are subsidised, and others not! In Austria, the use of absorption chillers with waste heat utilisation can be subsidised, not the conventional compression chiller.

- Carefully assess your customer potential before starting and once you have started!